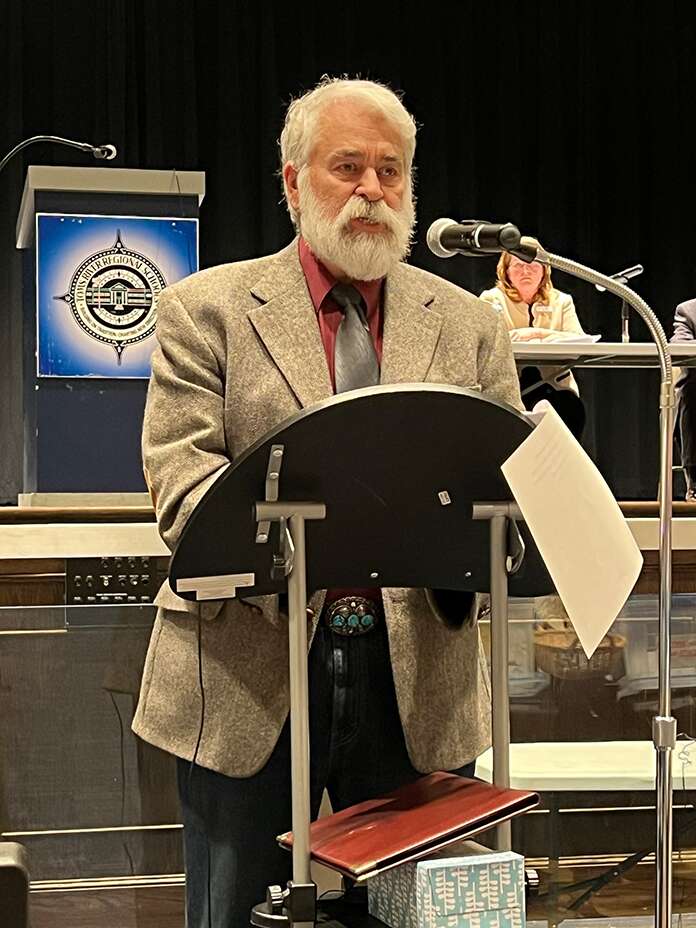

TOMS RIVER – Matthew Kelly made a quick stop in the pouring rain before he headed into Toms River North High School to attend a community meeting on a proposed settlement regarding the Ciba-Geigy superfund site.

Born and raised in Toms River, Kelly was on familiar turf as both a graduate and former teacher at the high school. Unfortunately, with some memories still haunting him, Kelly decided to momentarily pause by the flagpole at the school’s entranceway.

“There’s a list of students that have passed away while they were students here,” shared Kelly. “I stopped and read my cousin’s name. My uncle’s daughter died when she was 16 and a student here. My dad died of pancreatic cancer.”

Kelly said both his father and uncle worked at Ciba-Geigy back when it was Toms River Chemical. When Kelly heard about the plan for the superfund site, his first thought was he’d stay far away from it. Kelly then decided to join in the public discussion opposing the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP)’s proposed settlement.

He wasn’t alone.

Save Barnegat Bay sponsored the public forum in response to the NJDEP’s announcement of a proposed settlement with the site’s current landowner, BASF. The state agency generally allots 30 days for comments on what are known as National Resource Damages (NRD) matters. That date was extended to sixty days after pressure from local community leaders.

Britta Forsberg, Executive Director of Save Barnegat Bay, opened the presentation with some disturbing facts. The EPA reports that sixty percent of the contaminated groundwater plume remains, with some underneath the communities of Cardinal Drive and Oak Ridge Parkway neighborhoods.

“We are concerned about potential threats to future development and contamination there,” said Forsberg. “The risk of having passive recreation on a listed EPA Superfund site is real.”

BASF plans to preserve approximately 1,000 acres of the site and implement ecological or restoration projects. The public would have access to the site for educational opportunities and passive recreation.

The current proposal does not include plans to tell the story of how a renowned pharmaceutical company earned its ill-fated designation as a superfund site.

A Brief History Lesson

J. Mark Mutter serves as the Toms River historian and is also a past mayor and township clerk. He said that when the Toms River Chemical Company came to town in 1952, Dover Township’s population was just 7,000 as compared to 100,000 people who now live in Toms River.

Many surmise the Switzerland-based company’s move from its Cincinnati operations to a rural and wooded area in the Jersey pines came with a purpose. How better than to hide what actually went on behind the dense forest.

When Mutter was the township clerk, he found a file on Toms River Chemical that contained a single sheet of paper from 1964.

“That fragile one sheet was a Dover Township resolution and agreement, granting the company a right of way to construct and maintain an outfall discharge pipeline,” Mutter said. “Extending from the plant’s headquarters at the western end of the township, through the township, under the township, under the Bay, under Ortley Beach, and out into the ocean at the eastern end of our town.”

A collective gasp went through the audience of approximately 100 people.

Mutter said he spoke with L. Manuel Hirshblond, who signed on as the Toms River clerk in 1967. After all, it certainly seemed odd that the file with the resolution had no memos or reports with it.

“He told me back then that Toms River Chemical ran Toms River,” recalled Mutter. “That’s one of the reasons why I think we’re here. I guess my friend Manny was correct.”

Not only was Toms River Chemical the largest employer, its employees were also involved in civic affairs and politics. The company did good things – like supporting the construction of what was then Community Hospital.

The legacy that passed from Toms River Chemical and onto to Ciba-Geigy overshadows the idea that either company acted in a spirit of benevolence.

A teenager in the 1970s, Mutter remembered days of swimming at the beach with friends and family. The water was often a murky gray color, and it was impossible to see your feet below on the ocean floor at low tide. The pipeline was visible several hundred feet out into the ocean.

The turning point was in 1984 when the pipeline burst under Bay Avenue and the rupture exposed the company’s operations to a wide audience worldwide.

“Years of controversy led to investigation, litigation and the end of production in 1996,” Mutter said. “In 2000, when I was the mayor, I publicly spoke about Ciba Geigy’s corporate and social responsibility to Toms River.”

Although operations at the plant had ceased, decades of illegal dumping remained. Mutter implored Ciba to donate the cleaned up property to the township for open space preservation and continue its clean up of the contaminated soil and the aquifer below.

Several members of volunteer organizations with impressive backgrounds weighed in with their knowledge, including Peter Hibbard, the president of Ocean County Citizens for Clean Water.

Hibbard said there was no environmental oversight when Toms River Chemical first came to the town. The disposal of toxic chemicals went directly into recreational waters for several years.

“We learned they were disposing of solid waste near the Manchester town line,” said Hibbard. “But nobody knew what was going in the ground.”

Previous employees of the company said the barrels of waste dumped at that location may still be there.

“Originally, the company’s liquid waste was discharged directly into the Toms River,” Hibbard continued. “Because the color of the wastewater matched the color of the sea of water in the river.”

Some suggest the whole set of circumstances amounts to big business literally getting away with murder.

BASF Enters The Picture

BASF ultimately became owners of the land and promptly filed a tax appeal, saying the property was damaged. They were awarded a $17.3 million abatement that fell on Toms River taxpayers – many who were already scarred by the disregard for clean water and soil from the company back in the woods.

By 2019, BASF decided the same “worthless” piece of property was good enough to construct the largest solar farm in New Jersey.

“BASF is receiving conservatively $500,000 a year as a result of this lease agreement,” shared Mayor Maurice “Mo” Hill. “With three five year extensions, BASF will conservatively make another $20 million over the length of that lease.”

BASF will also be permitted to market an additional 250 acres of land for a profit under the terms of the proposed settlement agreement. Hill believes that the property should be deeded to Toms River and preserved as compensation for the damage done to the town.

The Proposed Settlement

The six page document comes with some statements related to the hazardous substances dumped during the manufacture of dyes, pigments, resins, epoxy additives and other possible contaminants.

Authorities feel certain the clean up isn’t nearly done and called on the DEP to ensure that history does not repeat itself.

“The town has never been invited to participate in settlement discussions,” said Hill. “This is a case of David versus Goliath; and it’s time for the DEP to side with David, not Goliath.”

Hibbard suggested that approving the superfund site for recreational purposes would be analogous to Love Canal, where taxpayers could be burdened with the expense of harm caused by contamination.

“This land is not pristine, and it’s contaminated,” Hibbard reiterated. “The open space plan and the environmental facility proposed would be a desirable use of land as long as it had not been contaminated by the Superfund concerns.”

Christine Girtain, a Toms River high school science teacher and director, holds the impressive title as New Jersey’s State Teacher of the Year. She shared her thoughts on the proposal, as a lifelong resident and mother of school aged children.

Girtain recalled the year she was a sixth grader and Ciba Geigy sponsored a poster competition for kids to portray something on endangered species. Her teacher, Shelia McVeigh, suggested the kids should draw themselves since Ciba-Geigy was endangering their lives.

As far as the idea of an Environmental Center on the property, Girtain agreed with the other presenters. However, she added that if it came to be, it needed to be more than a history of the Pine Barrens.

“The kids need to know the history and the pollution that’s there,” said Girtain. “They need to know the names of the people that died from that.”

A future workforce could be trained on that land according to Girtain – with studies that address issues like clean water, sustainability and soil health. Top of the line labs could be set up to give tomorrow’s scientists the best set of tools.

How To Comment

The DEP is hosting their own meeting which will take place at the same location – Toms River High School North’s auditorium – at 6 p.m. on March 13. Additionally, the public comment period on the settlement has been extended another two months.

Comments about the settlement may be submitted electronically at onrr@dep.nj.gov. Comments will be accepted until April 5.

There is a way to comment on the settlement on the DEP’s site as well. The proposed settlement agreement between BASF and the DEP can be found here: nj.gov/dep/nrr/settlements/index.html

For more information on the site and the EPA’s remediation process, visit cumulis.epa.gov/supercpad/SiteProfiles/index.cfm?fuseaction=second.cleanup&id=0200078#Status